Jason Steidman - Lightsweetcrude

Jason Steidman (aka. lightsweetcrude) is a projection artist based out of Toronto, Canada. He has been working with projections since 2009 , and has collaborated with many different types of musical acts, participated in art festivals across Canada, and has had his projections featured in several music videos and films, including the controversial David Bowie biopic “Stardust” (2020).

Read on to learn about how he has been influenced by the Surrealist movement, his approach to art, and why he doesn’t like the term “light show”

Sophie: For my first question I normally like to start with how people got into Light Shows, but I I want to ask why, don't you like calling it a light show?

Sophie: For my first question I normally like to start with how people got into Light Shows, but I I want to ask, why don't you like calling it a light show?

Jason: I mean it is the historically correct term. Since the beginning, and you can wonder what the beginning of this art form or this practice is; You could go right back to what was called the Phantasmagoria of the late 1700s, early 1800s. That's a way cooler name. “Light Show” is the term that was used in the 50s when this sort of began, and that's something that should be underscored, it didn't begin in the 60s, even though that's like the most popular, iconic and well-known era of it. It was the 50s. It's always been referred to as light show, but I find that light show does not serve this art form well as a way of describing it or giving it credence as an art form.

When you say light show, it's very superficial. People associate that with either something that's totally supportive of another entity within a performance or show; or something that's completely superficial. If you actually Google “light show”, you'll find Christmas events that are displaying lights and stuff like that. One thing that this art form has had a lot of problems with since the beginning is being acknowledged as an art form. I just find that “light show” relegates it to something that's supporting something else like a band or a carnival.

.

One interesting quote that I came across when reading this really amazing exhibition catalog, there's an exhibition called “West of Centre". It covered art and counterculture in the West Coast from like 1965 to 1977. And a lot of things that happened at the same time. One of the things they do cover is, the “light show” and one curator referred to it as a “fugitive art form.” So why is that? Well, there's a number of reasons. One is, and this is really interesting, that once it's done, it's gone. If you didn't photograph it, there is no piece of art to sell. But also, “fugitive” is different from “ephemeral”. I mean, ephemeral means that it's gone, but “fugitive” is underground, it’s not acknowledged. It's considered not “for real”.

So, personally, when I'm asked, “what do you want on the poster or on the event page” I really push for “live projections by” or “projections by” and think of it as projection art as opposed to a light show. Because a light show does connotate other things. It isn't unique to what's being done here by the different artists that you're speaking to.

Sophie: I've gone down that path too where I've been doing gigs and I've had the same question. Like, “how do you want it marketed?” And I'll either tell people it's liquid light because that's a little bit easier to understand. Or I'll just say Projection Artist. Because people will ask me what I do, and they expect me to bring out these huge strobes and lasers.

You mentioned Phantasmagoria, but what drew you to “light shows” instead of other kinds of art?

Jason: Well, the first time I sort of even considered this or was aware of it, I was in a band. And I heard about an artist, I think a Canadian local, named Shary Boyle was friends with a number of people who were sort of in their prime in the 90s in Toronto like Peaches, and Feist. She would go out and have an overhead projector and “live doodle” to what they were doing. So I became aware of it with that and I wanted someone to do that for my band.

I even set up something where I had two different artists doing this on two different projectors. It was me and a bass player doing an improvised weird sort of collaboration thing as part of this. I filmed it and it taught me a lot about what not to do. Not in terms of what they were doing, but just in terms of how it would work with a musical performance. But that sort of was the beginning for me. I thought that I would figure out how to do these things and then teach it to someone else and have them do it for my band but it didn't work out like that, I eventually became kind of obsessed with it. The more I looked into this whole overhead projector thing, then I started getting into the stuff from the 60s, the liquid and all that kind of stuff. It's hard for me to imagine that there was a time that I originally got into this and wasn't even thinking of the '60s stuff.

Sophie: Do you come from an art background?

Jason: Not really, it’s something I’ve been into my whole life, but I come more from like writing and music. It’s something that I've been dabbling with since I was a kid, and even took a couple of classes here and there, but no, it was never a serious pursuit.

Sophie: Do you think that being a writer or studying writing influences the way that you approach art?

Jason: Definitely. The more you explore and learn about one medium or one area, it definitely informs other things. The deeper you go into one thing, and the types of questions you start to ask. That obviously that just opens doors, it opens ways of thinking. Asking certain questions makes you ask other questions and it just sort of opens things up that you take with you elsewhere.

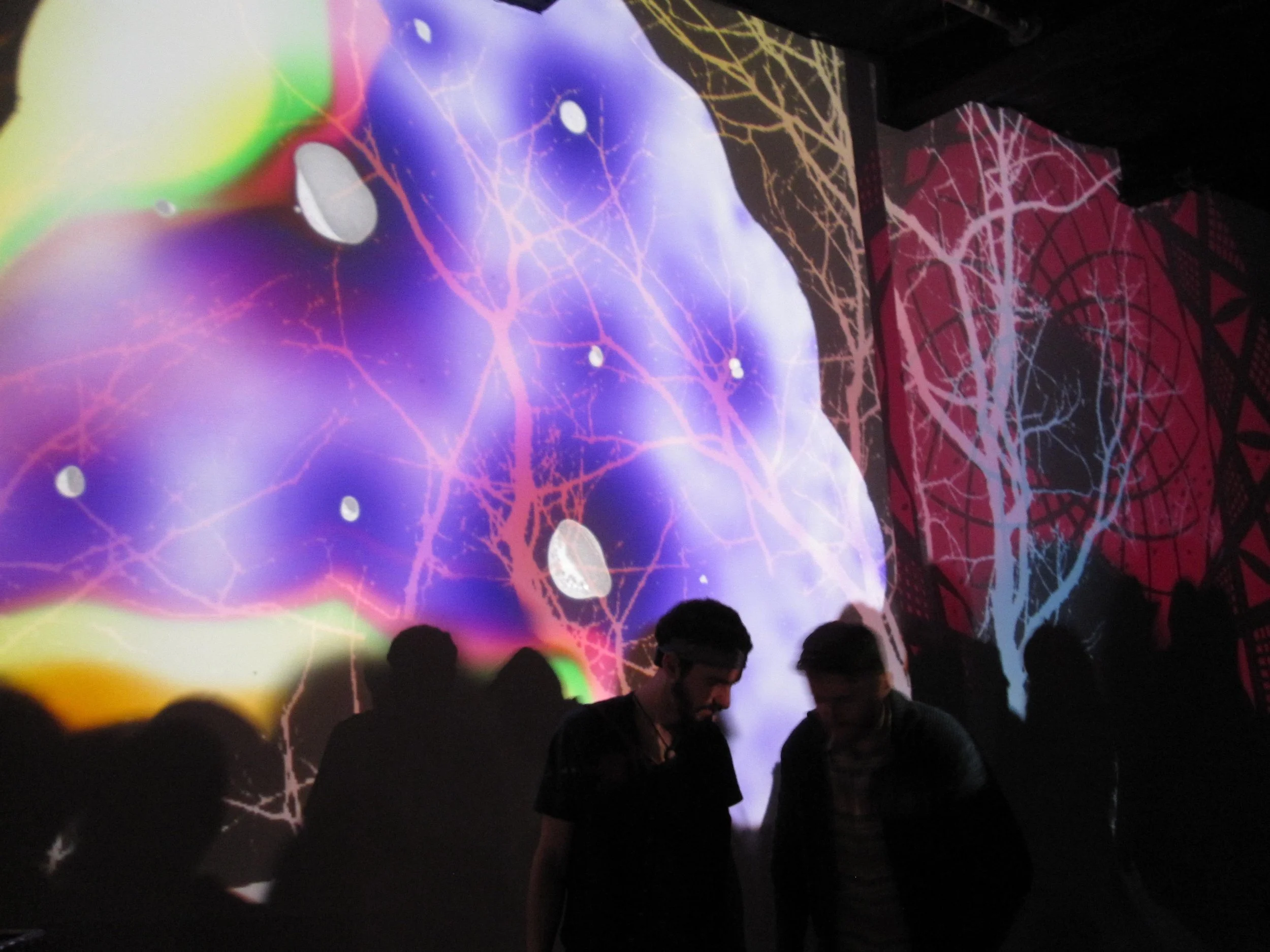

Sophie: I’ve seen online that you've done live installations. How do you approach that as opposed to if you were performing with a band?

Jason: Well, that's the thing, I find that it lends more credence to what we're doing when we're not an appendage to something else. There’s a lot of times I do art festivals and stuff like that, I apply and they have me back. And they almost always want to put me with a band. It's natural, I understand it. It’s been part of this art form since the beginning, but towards the beginning it was also paired with poetry.

How I approach it, there's a lot more freedom. You’re also responsible for a lot more. There is this thing that, if there's a band performing, I feel obligated, instinctively that I have to connect with that performance somehow. Which I'm not saying it's a drag , but there's no way around it. If you're doing something kinetic, obviously you're going to connect with the rhythm of the music. There's no way around that. If the music ends, you may feel that you’re obliged to either turn off your projectors, or pull the shades down on them for a moment just to acknowledge the ending of the music. I find that there's no way around that for me. I have to do that.

The time I mentioned where I was performing with the bass player and I filmed it, we hadn't coordinated the endings of the pieces. That was just something that I noticed, it looked terrible that the music ended and the projections were just carrying on regardless. So that's always stuck with me. If there's music going at the very least I have to acknowledge its tempo, its ending and beginning. I find that when you're doing your own thing, an installation is completely different. You're freed from all of that.

In terms of preparing, I don't know if I prepare it differently. Obviously, installations can be site specific. Maybe I'm bringing out more projectors because I'm covering a wider space, but in terms of what I'm doing in installation versus accompanying a band, the difference is more in how I execute the projections. I'm not relegated or restricted or tied to what the band's doing. I may be coming off like it's like a negative thing to have to do that. When it does connect, it can be amazing. And there's certainly benefits to it.

Sophie: What’s your setup like?

Jason: I operate by myself, and I use three overhead projectors, sometimes four depending on the situation. In the last year or so I've done two events that basically had vendors and booths everywhere, it was the cannabis industry. So they felt that I would be appropriate. The entire room was something I was invited to work with. Neither room was ideal, but at the same time it was great that, again, I was not tied down to this is the band, this is the screen, or whatever. And of course whatever screen area I'm given, if I can I'll go outside of it.

But the fact that It's just me and overhead projectors can make it a real challenge when you're working with a musical act to keep changing things up as opposed to exploring an idea for an extended period and having it morph, having it change. That’s why I find myself leaning away more from doing that.

Something else that I found really interesting, for a while, it was more rock bands or raves that I did, but now it’s normally completely experimental, improvised music. There’s a couple of organisations here in Toronto that I’ve been invited to collaborate with. That was really an amazing situation because everybody's completely winging it. To me in terms of collaborating with music it’s way more exciting, and way more rewarding. Because really, if you think about it, unless you know a band's material inside and out, they have everything together and they're totally scripted and choreographed while you can’t be.

Sophie: How do you approach being one person with three projectors? Do you ever feel the need to automate?

Jason: No, I've experimented with that. I have some mirror ball motors. I've built a couple things that rotate. I just found that it satisfies one part of me , it just feels like, “oh, okay, I've got something going on” but I don't really like automating stuff.

I found other ways to keep things evolving. I might look into it again at some point. I mean, I rotate things by hand. I have the ability to have three different things rotating, but it's all by hand, which I find I really prefer. Especially with music. I find even the speed of the rotation and the tempo are tied. Or they should be.

Sophie: So other than the rotation how do you keep the idea evolving, what techniques do you like to use to do that?

Jason: I have a lot of different stuff that I use, whether it's liquid, whether it's physical material. I have it lined up and I'm always thinking what I'm going to change stuff to. And you know it can be really simple. One thing that sometimes I'll do within a mix of a couple different projections is I'll have a plate, literally a plate that's empty, a glass plate, and I will start adding things to it slowly. And it could be transparent stones that I got from a stained glass workshop. It could be a feather. I just have a lot of different objects that are specifically designed to be added to something that's going on. Because a big part for me of what this is about is not just what is giving light, but what is taking away light. You could have cutouts of different shapes, different objects that block light, and all of a sudden those are creating shapes of their own.

If two projectors are overlapping and you block the light out of one of them, you're suddenly giving the other projector a little framed space.

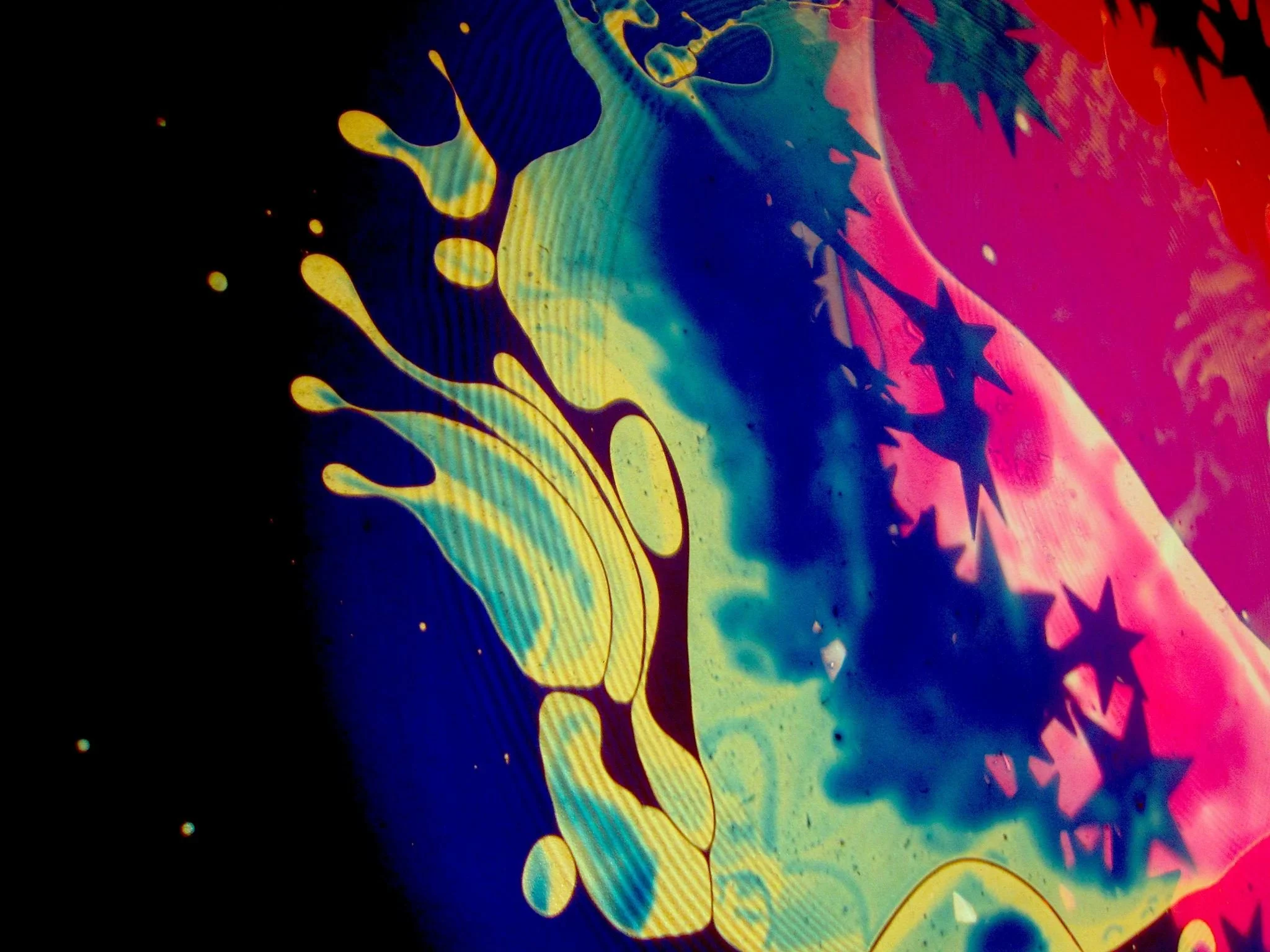

Just to give you an example, this is something that was evolving over quite a while. It was actually kind of hobbled during this installation or performance and all I had were three circular masks. I usually have many different types of masks, but I forgot all of them in Toronto. It's very upsetting. So you see that heart? That was just an object that at a certain point I just placed on the projector that’s doing the rightmost image. And it just allows that middle projector to cut through within the heart.

Sophie: I would have assumed that you'd done that digitally.

Jason: Oh cool. Well no. And I guess, is that a compliment? I guess that is because of the clarity and everything.

It's really weird because one time I was setting up for this band and one of the band members is sort of a producer, engineer guy, and this other guy who was hanging out as I was doing this, they were talking and they were just just blown away by how clear the image was from one of my projectors and they were like “that's so weird…you know I guess analogue for us [audio people], is something that's warm and fuzzy. But really, this analog stuff, [my projectors], is completely not like that.” It can be actually incredibly sharp.

Back to the picture, if you see those two shapes that almost look like fangs or rectangles pointing to the heart. Those are each just pieces of cardboard that I placed on that projector. So again, this isn't earth shattering or anything like that, but I mean, there's just a lot of stuff that I deliberately over the years accumulated, collected and continue to seek out. That’s just one element of the setup that’s evolving. Even just the type of liquids you use sometimes can change over the course of a half hour. You see right next to the heart on the left all that graininess that almost looks like sand or something like that, that wasn't there like within the first 10 minutes, over time that kind of started happening and evolving.

It's a great question because that's something that I'm always trying to elaborate for myself. I want the answer to that question, could be just having a host of materials that can slowly add to something to make it continue to change.

Sophie: So when I started doing my own stuff I started becoming kind of annoyed but interested by the role of the hands and seeing people do the show, because you're obviously placing these objects. How do you approach how much people can see of what you're doing?

Jason: There's so many things where, as the person doing it, or even as someone who also does it looking at someone else doing it, we want perfection. We want this thing to be just like a movie, we want to be able to edit out all stuff like that. But I have found that the audience really does find that interesting. It's one thing that draws them in about it.

I try and keep it to a minimum. Despite my just having said that and believing that, I try and minimize that absolutely. But one thing that I thought was really interesting, again, that same artist, Shary Boyle, I keep mentioning her. After I started doing this, I saw that she was doing something else, like a duo project with some artists, it was like her and this singer-songwriter/guitarist, and they would do these performances. They had named the duo “Dark Hand and Lamplight”, which I thought, that's so funny, she's completely just embraced, decided to live with the fact that the hand is inevitably going to make an appearance if you're using an overhead projector, At that point, it was no longer like live doodling, she actually had prepared these elaborate slides that you put on the projector of paintings and stuff like that. I think it had become a lot more scripted. She knew the music and had prepared all these like almost paintings to go with it, which is pretty wild.

That's just an interesting anecdote to what you're saying, is that you could completely embrace it, make a thing out of it. I found at a lot of these things people just approach me and just have no idea what it is that's going on. Sometimes they’ll look at me and I'll just point to the screen, they'll turn and look at the screen and be like, "Oh my God, I didn't even get that that was you doing that” I mean, there's live visuals, which this is part of, and that could be, you know, VJs and whatever, but I just think live projections, embracing that part of it is a cool thing, absolutely.

Sophie: So where do you pull your inspiration from? Like do you have references or is it just vibes?

Jason: When I began doing shows, and for a long time, Glenn McKay, Joshua White, Heavy Water, and the Single Wing Turquoise Bird were front and centre of my inspirations.

But also, art itself, even though I was never an art student, that's something that I'm always exploring. I'm always in the middle of one or more books and exhibition catalogs. All I do with Instagram is follow art galleries, museums, that type of thing. And even just sort of the philosophy behind types of art or artists inspires me in many different ways. Surrealism in particular, is something that I've been reading about for years. I took a course when I was in university but I can't even think of how many books on surrealism I've read because I find it fascinating.

I mean it's not actually a style, it's a working philosophy and I find it very inspirational and it feeds right into what I do and what I think a lot of people do but maybe they don't even know. One book on surrealism that I read was about how something called Biomorphism inspired surrealists. And the more I looked into that, the more I realized, wow, that's what a lot of liquids are like. They're biomorphic.

Sophie: I’d like to hear more about biomorphism and what other kinds of philosophies within surrealism you pull from.

Jason: I mean surrealism, there's been a lot of time defining it. It's just quite a rabbit hole, but there's a lot of different ways of thinking about what surrealism is. One of them is taking the world of dreams and considering that as subject matter. One of them is it's a working philosophy where chance is the guiding principle behind your output. Something that goes along with that is primitivism, getting back to a state where all of your learning, all of society’s, indoctrination, all that stuff is just put away. And chance feeds into that because when you have chance as a guiding principle, it doesn't allow for reason and refinement, and second guessing, and doing another draft or whatever. There's so much to surrealism. That's why I've been reading about it for years, because it's like, people will say, oh, it's not definable. They never defined it properly. It is definable, it's just very complicated. You can look at two different surreal art pieces and they look quite different, but it's also about how they were created. It’s the principles behind how the artists worked that makes them both surrealist. Salvador Dali’s style is what's considered to be the style of surrealism. A lot of people who became surrealist artists, both in America and Europe, were influenced by it. But, it's not the whole thing.

I find that, if you think about that, it could really guide the way of you're doing, even just things like the whole placing shapes on the projector. You could just say, okay, I'm going to put a bunch of different things into this bag and shake it up, and I'm not going to look, and this is what I'm going to do for like the next two minutes. I'm going to just grab things out of this bag and put it on the projector and wherever I put it I'm not moving it. Whatever comes out of the bag, in there, there's transparent stones, there's cutouts of triangles, there's marbles. And that's so basic and so unsensational and so un-world-shattering. But that that will yield something that you can't predict and you can't duplicate.

Sophie: I was reading recently, I think it was DaVinci, who he would just like throw his like paint rag at the canvas and be like, okay, whatever I can see in this is what I’m going to paint paint. Like, throwing the rag isn't really the sensational part, it’s what comes out of it, you know?

Jason: It's interesting that you should mention that because, even like Jackson Pollock, that whole thing. There are many academics who tie abstract expressionism to surrealism because a lot of the surrealists who had left Europe because of World War II, they were in New York in the same circles as people like Jackson Pollock and his contemporaries. To bring it back even closer, a lot of people consider liquids, liquid light projections, which began in the Beat era in the '50s to be a visual sibling to jazz and abstract expressionism . Abstract expression has always been considered as sort of the visual manifestation of bebop and jazz and the freedom and spontaneity of jazz which when you you think how free and spontaneous it became later it seems quite conservative in the bebop era, but at the time it was considered quite wild. It's hard to believe. But yeah, I mean, these things are all tied together and the earliest liquid light work done by people like Elias Romero were done in San Francisco in jazz clubs, sometimes with poetry. There were a couple different notable poets who were accompanied by Elias Romero and a band at the same time. I find that it's interesting how it all ties together.

Sophie: What you mentioned before about feeling the need to conform to the music, Light shows do kind of make more sense with experimental music or jazz. Being able to experiment together as artists, instead have to conform to what's going on.

Jason: Yeah, and say if you were saying going on tour with a band, then that might be different because then there's ways of working in experimentation and choreographing that. It was interesting because I worked for 15 years as a recording engineer and producer, and one of the last things I did was this band that I recorded for a couple of days. And then through some weird coincidence, I also did projections for them one night at a club. And, through recording them for however many days we spent in the studio I knew their music inside and out Even though I was sort of like, you know, poo-pooing the whole band thing I did it for a long time. But this is one of the most amazing ones because I knew every note they were going to play. So that, you know, that does make me feel that like it could be different if it was a thing where like you were going to work together for an extended period of time and really know everything that was going to happen. And also, for them knowing everything you're going to do.

Sophie: So after that, what would be your ideal setting to project, not just to show your work best but to also have the most fun.

Jason: That's a tough question, but I would love to do more outdoor guerrilla stuff, on like buildings, something I've wanted to do for a long time, is in a store at night rear projecting on a screen in the store windows. Like it's in a prominent populated area where there's like a lot of bars restaurants at night. But that’s just a very difficult thing to do, I mean who's gonna let you do that? Or even just on the side of a building. I've done it before but I haven't been able to do it in a while. It's something that I really enjoy doing it and would love to do more of because it's completely unexpected. It's completely spontaneous. Nobody even knows what the hell's going on, but a lot of people do see it.

Sophie:Where would you classify your version of a quote unquote “light show”? Are you a surrealist or would you give it a new name?

I consider myself influenced by surrealism and abstract art and all that kind of stuff. I think it's just unavoidable, that just the way that these things work with the way that there's always an unplanned aspect. I don't want to get into the whole analog versus digital thing, but that's one thing with using overhead projectors, or even just any type of projector or an array of projectors. I’m not an expert at Resolume, but I've experimented with it a lot it's not something exclusive to an array of projectors, you can get into blending in the digital world and have unexpected things, but I just find that the fact that you can overlap multiple projectors in different ways, change the overlaps spontaneously, hide part of one to bring out something else, that allows for that type of spontaneity and unpredictability, like a whole chance element.

If you’ve ever heard of the exquisite, corpse; That was just this game that Surrealists used to play where they would have a piece of paper and they'd give it to one person. That first person is supposed to draw something on the top quarter of a page, fold it over so that you can't see it, and then pass it to the next person. They don't open the page, they just draw on the second quarter of the page and they fold that over, and so on. Then you open it up and it’s crazy, the idea was usually that it was supposed to be a body. Each person did a different section of the body, but they had no idea what they were connecting with, what was coming before, what was gonna go after, and it would end up being this crazy looking form. [With projection art] It's never as pure chance and random as that, but I feel that that's a really important part of it. So maybe I wouldn't give myself that title of surrealist, but I think it is sort of a guiding philosophy for me.

Sophie: Do you think that you could do an exhibition of the exquisite corpse as a light show?

I've never thought of that, but you know, you just came up with a great idea. You should pursue that. I mean, get like three other people, and then each person prepares their projector that it's covered so it's not projecting, and then they all just lift up the flap. And then wow, then there'd be this exquisite corpse on a screen, like going horizontally. I was just giving an example of like hard locked in chance where you can't pivot. Whereas when you're doing live projections, you pivot constantly based on what's happening. But you know, hey, you know, this is how great ideas come up, just by accident like this.

Sophie: Since we’re running out of time, I'm going to go back to one of my classic questions now. What is the best and worst gig you've ever done. And why?

Jason: Okay, I don't, I don't have a best one. But the the craziest was very early on, it was friend, and I knew everybody in this band and it was like an instrumental, not jazz, kind of jazz. It was an art show that had this band and me, but there was also art everywhere. This really disgruntled tech guy said, “yeah, we can't, we can't bring the screen down”, and the band was like, why the hell not? And he said the screen will be like right at the edge of the stage. We never have the screen and someone on the stage at the same time, the screen just goes right down to the edge so it's like, when we show movies or whatever. So it's either a band or a screen.

And the band just said, well, you know what, bring the screen down. We're going to play behind the screen, and Jason can do the projections onto the screen, which is insane, like no other band would ever do that. So that, I mean, it's not the best one, but it's, yeah, it's like one of the most standout scenarios.

The worst one, I mean, there's been so many things. There's a thing in Toronto, “Pedestrian Sundays” and that’s where this one hip neighbourhood, Kensington market closes all streets for the day and into the evening- it's all foot traffic only and I've closed that out a couple of times doing projections on buildings. I've had winds take transparencies off, blow things right off, you know. That's still not the worst gig because those are still always going. So I'm just trying to think the worst one.

Sophie: It's probably good there isn't a standout one where you're still having nightmares about it.

Jason: Exactly, there was a thing where I was asked to do projections for a band from New York called Woods, who were kind of like a psychedelic,folk-y kind of band. And it was at a club where there isn't like an elevated area. it's not suited for this type of thing. But I set up like on the floor in front of the stage. Didn't even think twice about it. But the band that opened for them was this band called Parquet Courts. I didn't think anything about it. I I didn't really check out their music. I was really more thinking of the band that I was asked to be there for. Even though I was good to do some projections on this first band. But part of the way through their set, the kind of punk influence came out, and suddenly there was like this mosh pit forming, and people slamming and it was getting closer. It was like this whirlwind of people that were getting closer and closer to me and I was just like oh my god this is insane. My entire table, my projectors are going to be just destroyed. Like it's nightmare. And then these four huge guys who had come out for the band that I was projecting for, I didn't even know who they were, they just formed a line and just stood there guarding my set up and pushed the people away and just protected me. It was crazy.

So yeah, I mean, neither of them are best or worse, but they just absolutely stand up.